Q: What did Holden Caulfield do when he grew up?

A: He got a job.

That is the elevator pitch of my novel Not To Mention a Nice Life, reduced to two lines, a simple question and answer.

(Here is an excerpt that expands on the narrator Byron’s dilemma:

Something was wrong with me. I applied to the appropriate colleges and one of them accepted me. I applied to the appropriate graduate schools and one of them accepted me. I decided not to apply to any PhD programs (it didn’t seem appropriate) and so none of them accepted me. The unreal world of academia beckoned; the unreasonable world of reality awaited. Neither seemed particularly appealing and I found myself paralyzed: options aplenty, none of them especially enticing. And so I decided it was time to go underground for a while. I found myself serving the people who had the sorts of jobs I regarded with the ugly envy of the underclass. I made less money than I might have liked but I got more free drinks than I could ever have imagined. One way to see the glass being half-full is to ensure that it is always half-full. While I worked on emptying those glasses I came to the conclusion that money is wasted on the wealthy and retirement is wasted on the elderly.

Something was wrong with me. I drank myself sober and couldn’t commit myself to more serious indiscretions. I did the unthinkable: I started thinking about that unreasonable world again. I found myself skulking around the library, picking up magazines and thinking about that itch I could never quite scratch. I read an article about this world wide web. How ridiculous it all seemed. So this is what people do during the day? A million possible futures unfurled in unreal time, right in front of my not so open mind, none of them remotely appealing. There it was, I thought: it’s already over; I’m out of options. And then a funny thing happened. I got a job.)

Of course, I’m taking some presumptive liberties and the question would not be possible without the heavy lifting J.D. Salinger did to create Holden Caulfield in the first place.

My novel does not mention The Catcher in the Rye, does not in any conscious way imitate it and the invocation of Caulfield is only a conceit.

In fact, and for full disclosure, I’ve weighed in on Salinger’s novel (inspired to do so shortly after his death, in 2010). I concluded that I was perhaps a tad too old or insufficiently impressionable when I first encountered it, though I did –and do– love the short story “For Esme–with Love and Squalor”. Here’s a taste:

The narrator of this story is reeling from actual experience in the real world, so it resonates to a young reader about to enter it, and certainly a more mature reader who has seen and felt some of those proverbial slings and arrows. It is, for me, difficult to recall a more quietly coruscating image in literature than the narrator lifting Esme’s (KIA) father’s wristwatch, which has shattered in transit, out of the care package. The question, as the story ends, is: does that broken glass represent the narrator’s spirit, or will he rally to once more become part of the world?

Speaking of becoming part of the so-called real world, one of the reasons the instant classic film Office Space is so beloved is because it’s so real; it resonates with just about anyone who has spent a single day in the unreal world of corporate America. More, it retains a nostalgic vibe for its irreverent and accurate deconstruction of the dot.com error, I mean era.

To be certain, Office Space, and any work of art that attempts to take the piss out of our increasingly mechanized, complicated and incomprehensible modern world, owes a tremendous debt to Joseph Heller’s Catch-22.

Anyone who understands Heller’s masterpiece as the ultimate insider’s sardonic assessment of the insanity/inanity driving so much of military muscle is at once accurate, but selling it short. Heller is going after America, as a corporation, and his writing, while prescient, is also distressingly relevant, well into the 21st Century. In many regards, he understood the way middle management and their underlings would be used as proverbial cannon fodder (foxholes becoming stock-boosting rounds of layoffs), while increasingly isolated and aloof higher-ups would divide the spoils and conquer their 401-ks. Yossarian is our guide through this surreal hall of one-way mirrors, but it’s not the commanding officers, but the evil star of the supporting cast, Milo Minderbinder, who epitomizes what our country has become, and who has engineered the shift. It’s not by accident that the average employee wages have stagnated for decades while the riches of the executive officers have multiplied by factors that would be hilarious if they weren’t so horrifying. Making Monopoly money a real thing via stocks and shares and seeing profits increase as production craters has long been the American Way. For all the success stories from the dot.com era, we now have systematized a formula where the game is rigged to imperfection: CEOs are brought in like exterminators to kill a company from the inside-out, and then they parachute away with millions of dollars (and shareholder approval) for their efforts.

Suffice it to say, Catch-22 has informed my sensibility as a writer (and thinker) and has more than slightly inspired some of my writing. The corporate shenanigans in Not To Mention a Nice Life owe a debt of respect and gratitude to Mr. Heller.

And I think all of us, dot.com veterans or not, owe some measure of approbation to the iconic Steve Jobs, one of the few citizens who we can actually claim changed the entire world.

Certainly, the dot.com era and the online reality of the Internet would be very different (if it happened at all) without his input and influence. Here is some of what I said on the occasion of his passing in 2011:

While I’m congenitally disinclined to join the choruses of hagiographers anointing this outstanding marketer, salesman and genius as some type of saint, I’ll certainly throw my hat in the very crowded ring and concede that our world would be much different (and not for the better) without his influence. As trite as it may sound, Jobs did in many ways help transform fantasty into reality. For that alone, he is a monumental figure in American history and should be celebrated as such.

For now, it seems right –and human– to celebrate the life and accomplishments of a man who undeniably left his mark, and provided a past, and future that would be radically different (and not for the better) had he not made his mark. Equal parts iconoclast, counter-cultural guru and corporate crusader, he made a complicated motto (Think different) and turned it into a postmodern religion of sorts. We could have done much worse. Whatever else he did, Jobs thought differently and in the process, took much of the world with him.

It’s easy enough to admire (and envy) the abilities and lifestyles of the great artists, especially the ones talented (and/or fortunate) enough to actually make a living out of making art.

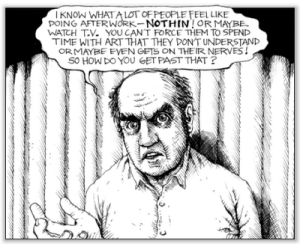

For me, I take a special inspiration (and kinship and solidarity) from the folks who never had it easy, who struggled to make art and/or a living. The ones who plugged away, with little assurance of pay-off, artistically or otherwise. They did it, ultimately, for the same reasons anyone tilts at the creative windmills: they don’t really have a choice. As such, Harvey Pekar remains someone that anyone with artistic aspirations can appreciate. In the excellent film about his life, American Splendor, he wakes up from a nightmare, and then remembers he still has his job. He actually stops to appreciate that he can pay his bills and understands how much worse things could be. In that one scene he provides proper perspective for all the naval-gazing narcissists who feel the world owes them a living, and lament that the world is so full of imbeciles who can’t appreciate their genius.

Here’s some of what I wrote in tribute to Pekar, when he passed, in 2010:

And while Pekar was groundbreaking in a way for making the primary source of his subject material his own life, his life story is more remarkable than anything written by or about him. To go from a genuinely obscure misanthrope living in squalor to becoming the mostly obscure misanthrope living mostly in squalor…that’s America. It’s definitely the American Dream, through a broken glass darkly.

It’s almost impossible to envision now, with everyone’s daily trials, tribulations and ablutions the focus of a billion blog posts, or the solipsistic Greek chorus of the Twittering class, but what Pekar did, then, by pulling the soda-stained cover off his personal life in the service of art was a revelation. Certainly, the subject of our immortal Self goes back to cave drawings and Don Quixote, and only official autobiographies are truly fictional. But when it came to the more postmodern type of tilting at windmills, Harvey Pekar was the patron saint of the unshaven, recalcitrant crank (actually crank is too harsh by half; he was more misanthrope who looked at life the way a chronically ambivalent dieter regards that piece of cake: he knows better but he just can’t help himself).

To become a meaningful artist one must be intolerant of cliche. To become a meaningful human being one must be intolerant of untruth. Although it came at a considerable cost, Harvey Pekar was incapable of cruising along the soul-crushing streets of quiet desperation. In becoming the poet laureate of disinclined endurance he helped remind America that there is a splendor in our shared obsolescence.

(an excerpt from the novel)

These day trips ask a lot of you, almost so much that you find yourself fondly reminiscing about the good old days you never knew, the days when horse-drawn carriages were cutting edge business travel, days when people might have fantasized about a few hundred miles in less than an hour, not anticipating planes that make your mind feel microwaved.

Cooked on the surface but still raw inside, it’s all in a daze work as the cab carries me home through disorienting yet familiar streets. Survival suburban-style; a metropolis in transition, trying its best to live up to the image it was designed to imitate—sprung from the minds of forward-thinking people who are trying to recreate the past. On the corner high school punks stand beside a phone booth, making no calls; a quick right turn and I’m feeling the money dread as we cruise past several blocks of four car families. Being outside the city is safer, particularly if you prefer the sound of crickets to cop sirens. Eventually, I’m deposited in the middle ground of this middlebrow town, and for lack of any other options, I am relieved.

And yet. This is supposed to happen later, with wife and kids and a basement to be banished to after hours. I’ll deal with that later. I think.

My front door is the one mystery to which I have the key, but for some reason I still feel as though I’m sneaking up on a stranger every time I return from a trip; I’m not sure who I expect to see, who might be hiding from me, who possibly could have found the way into my modest refuge from friends and memories.

With Pavlovian precision, I make my way to the medicine cabinet and pour myself a bracing plug of bourbon. It’s more than I need or deserve, I think, but I don’t want the bottle to suspect I was unfaithful in another town, waiting for my return flight for instance, in a cramped and crappy airport bar at La Guardia. If this were a movie (I think, mostly in the past, but even today), I would grab my crystal decanter, filled with obviously expensive spirits, and administer that potion the old-fashioned way, needing no ice cubes, especially since I would never get around to drinking it, as it’s only a prop, a cliché. No one reaches for that tumbler these days (except in movies); the question is: did they ever? Even in the 50s? Or has it always been part of the script?