The Olympics, particularly the two most popular sports from each season—the gymnastics and figure skating—sells itself, accurately, as an embodiment of competition and tension, complete with a touch of voyeurism. More, these spectacles have proven to be immune to generation or fad, as they synthesize several of America’s favorite obsessions: rivalry (friendly or not), physical prowess and especially the zero-sum proposition of win/lose. And then, the added bonus that makes these events irresistible: the enduring possibility of abject humiliation on the largest conceivable stage.

It’s a curious ode to evolution if you think about it. What likely began as gladiatorial combat—and as stakes go, they don’t get any higher than that—gradually became uncomplicated challenges to see who could throw the farthest, run the fastest, hit the hardest. Eventually the endeavors became more complex and stylized to the point where we now have synchronized routines measured on an Aristotelian ideal that can never be attained, at least in any pure sense. We are, after all, talking about human beings engaged in activities judged by other humans. And yet that element of subjectivity is a subtle reminder of our fallibility. All the world’s a stage, let the best one win and allow us to measure the glory and the disgrace. This is what compels us to watch.

What viewer, however indifferent, is incapable of imagining the dedication and sacrifice inherent in these exhibitions? The interminable hours of practice, the inconceivable monotony of repeating the same motions days after day for months that offhandedly slip into years, sacrificing leisure and even identity for a single-minded compulsion. What is staggering about the commitment any of these sports require is that the time is not devoted merely to the pursuit of excellence; it is about being the absolute best, in the world, at something that many other people do at an impossibly high level. Consider what it must feel like to become at once smaller and larger, as a person, perfecting oneself in one specific way, while everything else in the world changes. It gets hot, and then cold, friends get fat, flunk tests, have sex, make babies, go on adventures, get married or divorced, get practiced at being imperfect and learn to speak the language of life. And you are like a monk, shrouded in the frantic sameness of actualization, repeating the same urgent prayers forever and ever until eternity…or victory.

Then consider the art of improvisation. It is at once the epitome of skills developed through practice, and the apotheosis of the very freedom—of form, of content—that a well-rehearsed routine obviates. Put in a less pointy-headed way, a live jazz performance is exhilarating in ways that are both similar to and opposite of Olympic competition.

We want to be astonished, and surprised: jazz invariably delivers. In order to play the music in the first place, sufficient mastery of the various instruments is obligatory. The practice, the woodshedding, is not dissimilar to the hours alone in a gym or a pool. In Olympic action we hope to see perfection; with jazz improvisation we want something beyond even that. We want possibility, we want to feel the kind of connections that speech and prayer and sentiment—however sincerely conveyed—cannot quite capture.

Reflecting, earlier this year, on one of the best and most important jazz musicians of the 20th Century, drummer/composer Max Roach (full tribute here), I wrote:

While there is much to admire and recommend in the excellent documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, especially for young creatives or academics who want to better understand–and appreciate–mastery and what it involves and requires, there’s one sequence that has stayed with me. The apprentice chefs are on rice duty before they even touch fish, and this doesn’t involve a single shift, or a week, or even a year. It’s three years of making rice in order to earn one’s place at the sushi station, where one might spend another five years training. And better still, all this obsessive training and refinement of craft isn’t to make a particular piece of fish taste better or different; it’s to obtain the necessary skills to be sufficiently prepared, to indeed be worthy of the appropriate pieces of fish. In Jiro’s kitchen, the presentation is simple, unpretentious, authentic to the point of resembling something more spiritual than culinary. Therein, generations of the highest achievement teach us, lies the secret. Which is: there are no secrets; there is repetition, respect, compulsion, perfection.

Thinking of this rough algorithm is, it seems, at once more eloquent and immediate than the by-now tired cliche of 10,000 hours. But let’s consider 10,000 hours as a reasonable baseline for approaching expertise in a particular task—that emphasis on repetition and consistency the key to fathoming how one upshifts from good to great. It’s also a useful corrective for our contemporary discourse, where shorts cuts and “hacks” have replaced what we might simply call old-fashioned discipline. We see the ideal baseball swing or the method actor’s award-winning scene, or even the deceptive simplicity of a smart phone’s interface and forget it’s invariably what happens—and for how long—behind the scenes that makes the most complex movements seem unforced, inevitable. How many free throws did Michael Jordan shoot, alone in a gym or in a dusty driveway in all kinds of weather? How many lines of dialogue did Hemingway write before he arrived at his minimalist style, still imitated more than a century after it made him famous (and infamous)? How many times did his brush touch a canvas before Van Gogh began to master the ways color can invoke mood and feeling? How many times did Max Roach hit a high hat before he became the most brilliant and accomplished drummer in history? Well, if during any routine practice session, he’d touch each instrument in his small kit one hundred times, which is an exceedingly conservative estimate, that would make about 36,500 times a year; add up those flicks of the wrist along with the hours, and the picture comes into focus rather quickly.

How many times had he played that kit, preparing himself for this occasion, to make it sound like the Platonic ideal of percussion on the title track of his album Quiet as It’s Kept, as close to perfect as any recorded drumming has ever sounded?

Perhaps the combination of ceaseless practice, the simple (and profound) dedication to craft, the single-minded obsession with unity of sound, is nowhere better represented than in the man who played the saxophone better than anyone has ever done anything, John Coltrane. From a piece I wrote a couple of years ago, I commented on the ways in which, even after Coltrane composed what were universally considered masterworks, he kept pushing himself. His drive was so relentless it became difficult, literally, for his audience to keep up with him:

After 1960, one can hear the imprint of Ornette Coleman alongside the harmonic algebra of Monk and Miles, all bubbling under the surface of an increasingly intense and emotional approach to songwriting (and soloing). Rashied Ali, who worked closely with Coltrane in the final years of his life, compares him to a competitive athlete: “He was like a fighter who warms up in the dressing room; he’d break a sweat (backstage)…he was always playing.” This combination of restless energy and relentless exploration led to concert experiences that were as exhausting for audiences as they were for the musicians.

(A lot more from me on John Coltrane here.)

And this leads me to…Jay Adams.

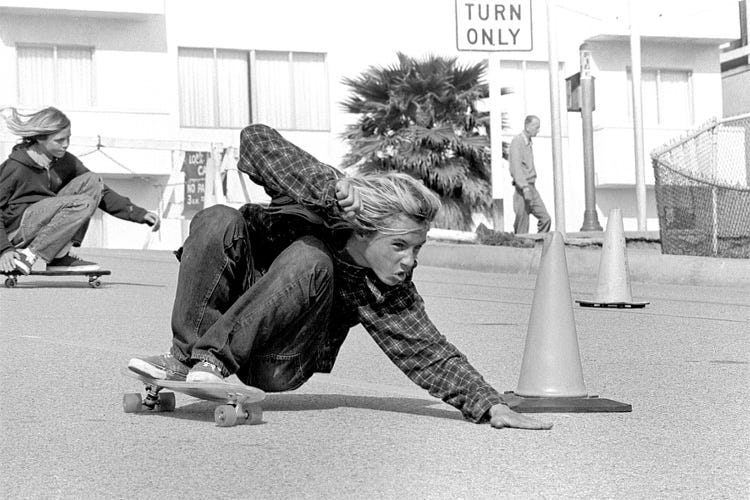

If you don’t know who that is, you have not seen what I consider one of the best documentaries of this century, Dog Town and Z-Boys.

There’s an incredible sequence that would be instructive enough, if only related by the many eyewitnesses. Instead, and more than slightly miraculously—considering the time and circumstances (1975, a skateboarding competition)—it was recorded and we can actually watch it. We can see what happened as the participants reminisce about what went down that day.

To me, this remarkable moment captures, in sport and culture, a paradigm shift that echoes similar seismic changes instigated by some of our best musicians and athletes over time. But what really resonates—and I’m fairly certain this impression was facilitated by watching the Olympics these past two weeks—is that it’s difficult to imagine an event that more perfectly synthesizes the aspects of practice and improvisation: Jay Adams’s epic skate routine heard ‘round the world (or at least the underground, which is always where the magic begins) is sui generis. It’s a moment he owns, and it’s a moment that defines the skater and the sport. The sport he helped reinvent was never the same after he had his way with it.

In closing and because I can, I’ll seize any opportunity to invoke Charles Mingus, an artist who in my opinion came closest to perfection while consistently insisting on the power, freedom, and possibilities of improvisation.

Here’s one poem of many I’ve written celebrating Mingus, and anyone who follows me knows The Mighty Charles Mingus is a well I return to often, and his music & life are a ceaseless font of inspiration. Check out the video, below, of this miraculous collective laying down some incendiary, healing improvisation. (More Mingus poems here, here, and here.)

The Charles Mingus Sextet in Europe, 1964

Another day at the office: six musicians assembled

so close together they’d almost fit inside the piano—

all dressed like they’re about to give away the bride.

Imagine if baseball teams had to wear the uniforms

businessmen did throughout the twentieth century:

coats buttoned up and their ties too tight at the neck,

a signal that serious work almost always gets done

when people are made as uncomfortable as possible;

the same kind of illogic that drives or else stymies

innovation and all things, except art. What if the game

itself was played in the dugout, pitches, hits, and catches

happening elbow-to-elbow as the sweat flowed, turning

improvisation into art on the fly, rules ignored and belief

bolstering a faith to convince skeptics we’re all immortal.