Speaking of Anthony Bourdain, who was recently and lovingly remembered here, one of the many things that made him noteworthy was the light he shined on the real workers inside restaurant kitchens. Before and after he went All-World with Kitchen Confidential and the celebrity that followed, in America we’ve had a fetish for the rock stars: the owner, the maître d', and especially the chef. Entire series (some excellent, some insufferable, many a combination of the two) are dedicated to the exploits of these knights in white jackets. (Not unlike how the myriad hospital dramas focus on the doctors and less so on the nurses or administrators or especially the masked and gloved armies who do everything other than operate and make decisions—and earn huge paychecks.)

Who sings the songs of the line cooks, dessert makers, those who man the salad station, the dishwashers? Nobody. Those roles aren’t sexy, and there’s no money (made or to be made) showing how the sausage is assembled, cooked, and cleaned up. Bourdain, having patrolled all those stations, made it a point to acknowledge those who stand behind the chef—and not because it made him look cool, but because he knew: without these industrious and indefatigable soldiers, the entire machine breaks down.

One of the reasons, I suspect, that The Bear has resonated so powerfully, aside from the excellent acting and (usually) competent writing, is the fact that the drama does more than offer fleeting or grudging drive-bys of the workers who all too often are nameless, faceless, and uncelebrated (like the vast majority of blue collar workers who make the proverbial—and literal—planes, trains, and automobiles arrive on time). I wrote a bit about some of these folks, which also gave me the opportunity to appreciate George Orwell (in general) and his masterpiece Down and Out in Paris and London (in particular) several years ago (you can read it here).

This is a poem that works (I hope!) as a standalone piece, but is also part of a work in progress—a cycle of poems about “the business” as we used to call it. I’m grateful to the excellent journal Five South (check them out online here) for publishing this one in April.

Short Timers

They come and go like whatever’s sold as the fresh catch that week, and occasionally don’t even last that long. The ones who have barely clocked in and begin asking about first cut, meaning another server will cover their tables; one who needs the money or knows enough not to arrive at the bar too early. A server who understands drinking all your tips away is stupid, drinking more than you make unforgivable. These are the short timers, who work because there’s nothing better to do, or whoever actually pays their bills makes them, telling them they have to at least try, to make some contribution to a bottom line that never needs calculating because the only money that matters is what’s being earned in interest. These often-uninteresting people who inherit consciences clean as the chef’s station after last call, who only sweat when they’re asleep, who understand the slow animals born without teeth are made to become meals, if ever asked what they worry about will smile as if reality was a dinner tab that arrives at the end of one’s life, as if that entire meal wasn’t on the house.

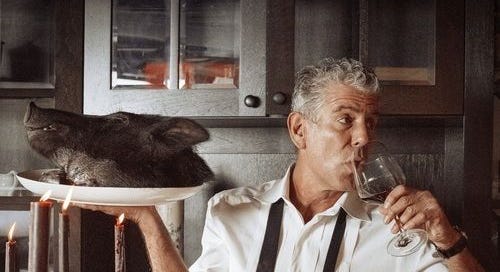

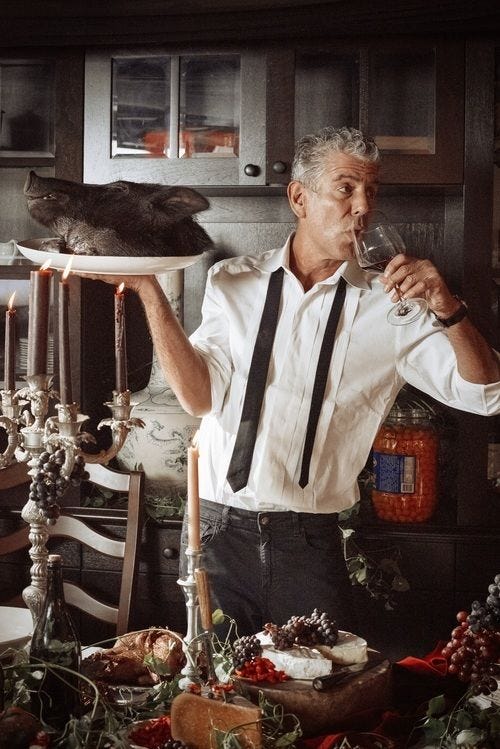

More Bourdain (above) and more about “the business” (below). This is also excerpted from a longer series of reflections, and this piece was published by the amazing team at Exterminating Angel (another wonderful journal I’ve had the enormous privilege of appearing in many times) back in 2022.

ii. 1987

Believe in God?

You didn’t even like The Boss when I first met you, back when Born in the USA made you break out in hives, you insisted.

Only B.S. I’m trying to hear is Black Sabbath, you swore, the certainty of an older brother not by birth, the refusal to suffer the foolishness of Top 40 or anything any priest or politician said.

Teachers too, you warned. I know you plan to go to college but be careful about those mind-fuckers, all of them allergic to an honest day of work.

Unlike you (you implied), with your kitchen whites and black boots making their blue collared statement. Put any of them in front of this grill and they’d wet their pants. The pride and prejudice of a kitchen grunt, a baked-in scorn for everyone you served, especially the front of the house—who had to shave each shift and wore cologne like gay bohemians in some French bistro. I too would have been a sworn enemy on sight, a bus boy who didn’t mind sporting some Old Spice on occasion, but we spoke the same inscrutable language—the one found inside the grooves of 70s LPs.

1967 was the peak of civilization, we agreed and anyone dumb enough to enjoy Top Gun or believe Oliver North was a sucker, a sellout, or worse. I never admitted I envisioned law school and an imported convertible blowing a silk tie over my shoulders as I cruised home from the court room, somewhere in California, almost certainly. With Led Zeppelin cranking from the cassette deck, which was all that ultimately mattered, we knew, in our eyes and especially our ears.

Ours was the kind of friendship certain males have, bolstered by a mutual love of beer and music. You saw yourself in me, you said, and I understood. It’s not that I saw the same so much as I hoped I’d inhabit your insouciance. I couldn’t understand the glow of this certainty that attracted me, like a moth, even as it would burn me if I got too close; if its heat got under my thin, well-kept skin.

We saw the Moody Blues, already an oldies act but a living connection to the lives we missed in real time. The show was shambolic but I bought a T-shirt anyway, a statement to make amongst the flat tops and Top Siders I navigated around each weekday, a minefield of male aspiration and entitlement.

You smoked weed like you were exterminating evil spirits deep inside (and for all I knew, you were). The emanations of your habits, either a halo or else disinfectant for everything boring and banal. I saw you as an original, not yet old enough to understand you were rejecting alternate realities you’d been denied. I was still young enough to believe in the American Dream, unaware it was an RSVP sent only to those already running a tab.

This was an era where everyone drank the same beer but smoked a different brand. And everyone smoked. In other words, it was the opposite of today, aesthetically. Marlboro Light, the Top 40 of cigarettes, the Muzak of vices: for people who liked their nicotine the way they liked their beer or food or art: watered down, safe, predictable.

Speaking of unpredictability, I came to work one day and you didn’t.

Questions: where did you go and why did you leave and what are you doing and how did you get there? Where do people like you see themselves in five years when they live in five-hour increments, punching the clock until they punch out, permanently.

Prediction: you never found yourself pulled out, in pieces, from under a car or setting up shop at some unsavory street corner—purgatory with a paper cup—where anyone who knew you pretended not to see. Not that you were staying in the same city for too long, running because that’s what people like you do when they’ve run out of money, run out of friends, run out of options. Just like those gods from a different time we worshipped and hoped to become, you never realized the best years had already happened, like them you never saw it coming. And maybe you took it in a stride you learned to accommodate, obliged to live and bear witness in battles few others are made to fight. Alone everywhere in the world but willing to endure, one drink, one smoke, one setback, one more experience that will drive lesser sorts insane, at a time.