It was my extreme pleasure to chat with Sarah Trembath for Some Things Considered (Season 1, Episode 5), as she and I have been in conversation on a number of topics, including academia, politics, and, of course, writing, for many years. I’m honored she took the time to conduct a recent Q&A around This Kind of Man, with a specific focus on my treatment of toxic males and, inevitably, the current tensions around the American presidential election. As a reader and fan of the Washington Independent Review of Books, it’s a real thrill to share this feature (I’ve pasted it below, but would also like to drive traffic toward their site, so please check it out here).

Hi, Sean, Thanks for joining me.

Sarah, it’s always a joy to speak with you. Thanks for this opportunity.

As you know, I’m really tuned into your renderings of the inner lives of men and your portrayals of men in various stages of self-awareness. What are you bringing to the conversation about maleness? What do you think that your body of work adds to the literary treatment of fathers, in particular, in literature?

My latest book, This Kind of Man, interrogates toxic masculinity from a variety of angles, and while I’d maintain no punches are pulled and no easy excuses offered, I also wanted to dive more deeply into the fact that men who perpetuate damaging behavior have themselves been damaged. In this regard, we can look at toxicity through generations as a sort of perverse inheritance. We’ve seen many monstrous fathers in literature, from Dostoyevsky to Conroy, but I think it’s both interesting and useful to explore this dynamic with compassion and not feel smug, dismissing certain types of males as hopeless or evil. I look at moral cretins like Elon Musk or Donald Trump, two powerful men who epitomize all the worst aspects of male toxicity, and recognize that they were never shown love by their own miserable, malevolent fathers. This pathology goes back to Adam and his sons in the Bible.

You are a master storyteller. You are also one of my favorite contemporary essayists, someone I make time to read. I see you as what Gloria Anzaldúa might call a border crosser (of gendered experience) and an interlocutor between generations of men and between men and others.

Well, first off, thank you so much for your exceedingly kind and generous estimation of my work! I can trace my style, as such, to a combination of factors: having been raised by loving and progressive parents, I developed an empathy, and that always complemented an intense curiosity. By the time I got to grad school, cultural studies and deep reading of theory and literature gave me an insatiable appetite to not only identify the root causes of issues, but to explore them from multiple angles and never be content with easy, cliched solutions. Many writers are obsessed with injustice and have two primary compulsions: to find meaning (and truth) within the haze of propaganda (and cultures dominated by the twin forces of political and religious ideologies), and to use this energy to identify with and advocate for those most ill-served by contemporary power structures. When I first grappled with what patriarchal societies are and what they do, I could never not see this. As such, it’s been imperative, for me, to constantly explain, debunk, and, whenever possible, ridicule or ameliorate it.

I feel that! As I was reading your newest work, I was most tuned into how some of the stories in it reflect your commitment to nudging forward a new masculinity without oversimplifying the predicament. Self-awareness and societal awareness surface over and over in your treatment of your themes. Why those aspects of the problem?

As I mentioned earlier, there’s plenty of blame to go around, but I think it’s fair and accurate to say that it has [been], as James Brown semi-facetiously declared, “a man’s man’s man’s world,” and we see what that’s wrought, occasionally (if not often) for the worse. I feel fiction can home in on the symptom but then magnify it or dramatize it from a variety of angles — this has the power to diagnose it and take away some of its power. To be specific, I think this is all very political: Once enough men figure out that “the system,” while traditionally set up to privilege them, also uses them up and pisses them out, that by being part of an abusive structure, we allow abuse to everyone, including our families and ourselves.

Beautifully said. Shame comes up a lot in your work. You have an interestingly complex take on it — it’s as problematic as people think it is, but it seems to function well as a guardrail against bad behavior. Am I getting that right?

It’s interesting: I can scarcely relate to most of the characters (the sons, the fathers, the angry or confused dudes) in this collection, so part of the impetus for this project was to try to satisfy my own curiosity. As a starting point, having known many men who have been friends, friends’ fathers, coaches, teachers, etc., I have had the benefit of knowing them in full, so if I consider unsavory things they’ve done, I extend a certain grace I might not to a stranger.

I wanted to “crawl around” in the headspace of men who do unspeakable things, especially those who know better but can’t help themselves. I think there is a profound shame that not only results from violence but also precedes it. Many of the men in this collection are dealing with shame, and that leads to things like alcoholism or narcotics or divorces or fractured relationships. At the same time, a very basic sense of shame kept our culture somewhat in check. I think the last decade has proven, to our detriment, that the truly shameless can be unaffected by it, and Trump has illustrated how to just power through the initial shock and, unbelievably, turn it into an advantage. One hopes we have a tipping point, and some good old-fashioned shame returns as a modifying force in our society.

In “This Kind of Man,” the “sins” are so much less vicious than they are in pieces like “Gethsemane,” where we’re looking at an unrepentant adulterer and problem drinker dying more or less alone. In the title story, though, our protagonist is a widower who realizes how much more domestic work [than him] his wife once did and what that cost her. As he’s working through it, he needs the orderliness of recipes (as opposed to religiously inflicted shame) to help keep him in line. Can you speak some to your artistic choices in that piece?

“This Kind of Man” is one of those exceedingly rare mini-miracles, artistically speaking, that seem to spring from nowhere.

Oh, I love those!

I wrote that story pretty much in one sitting, without much forethought. It’s not based on anyone I know or have heard of but it had to come from somewhere, and I don’t just mean my imagination. I suspect the energies informing that piece are, like the story that opens the book, a sort of catalog of men I’ve read about or heard about, and the sum total of all this toxicity found some type of modest release when I opened the creative floodgates. I can’t take much credit for any artistic choices, whereas in a story like “That’s Why God Made Men” or “Red State Sewer Side,” I knew that to make the narrative resonate, I’d have to deploy a woman’s and child’s point of view, respectively. For a story like “This Kind of Man,” it had to be straight, no chaser: no ironic detachment or distance. This story had to be taken directly from this guy’s brain as if he’s dictating from a confessional or deathbed.

Your cover is phenomenal! It’s dark in the background, with a profile of a man’s face. He’s at once peeled back to his facial musculature and simultaneously adorned with various decorations. His crown is either made of fire or it’s on fire, and his chin is held up by a chalice. Can you put it in conversation with the stories? What is the cover doing?

You are the first interviewer who has asked about the cover! Thank you! So, [for] this collection focusing so claustrophobically on toxic males and their attendant violence, it seemed imperative to find an image that conjured up pain (directed inward and out), conflict, and some sense of the historical naturalness of this condition. I am fortunate that my publisher, Unsolicited Press, agrees that the author should have some say in their cover art, and I took this mission very seriously. I spent months trying to find or design something that would work before I stumbled upon “Fire” from Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s “Four Elements.” I knew immediately. It’s a stunning image, and when one considers he painted this in 1566, it’s astonishing on so many levels. I mentioned before that these “daddy issues” are as old as we are, so I suspect the image of a guy with his hair not only on fire, but made from fire, is so perfect, I feel inadequate to offer further comment.

Gorgeous. We could go on forever about this kind of thing, but we’ll have to leave it here. Can you leave readers with one statement about story? Tell me in one sentence why story is such an important medium for the change we seek in this world.

Stories denote truths that are outside time and agenda, wherein we discern the uneasy lines connecting our shared histories and possible futures — and they provide otherwise elusive opportunities for recognition, empathy, culpability.

Wow. Thank you, Sean!

My pleasure, and thank you again!

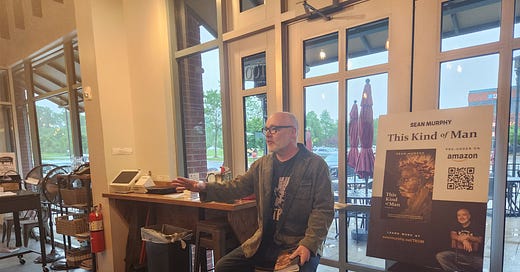

Bonus video: