Our Artists Will Be There (As Usual, As Always)

Art is resistance and resistance must become artistic

Yes there's data to crunch and yes we need to adapt and yes we need to tell better stories and prepare for new realities but there's also very little new under the sun: just remember that The Buk had these shitheels in his sights half a century ago.

Beware those who seek constant crowds,

for they are nothing alone,

beware the average man, the average woman,

beware their love, their love is average,

seeks average,

but there is genius in their hatred,

there is enough genius in their hatred to kill you,

to kill anybody,

not wanting solitude,

not understanding solitude,

they will attempt to destroy anything

that differs from their own.

Not being able to create art,

they will not understand art,

they will consider their failure as creators

only as a failure of the world.

Not being able to love fully,

they will believe your love incomplete,

and then they will hate you,

and their hatred will be perfect,

like a shining diamond,

like a knife,

like a mountain,

like a tiger,

like hemlock,

their finest art.

One thing about Bukowski: he was not only not part of the academy or the elite, he was pretty much despised or ignored by those tastemakers and gatekeepers and, fortunately, he eventually had enough success that he didn't have to rely on their insular, priggish, elitist (yes, elitist) cadre for support or approval. And he had them in his sights. But since he lived and breathed and struggled amongst not only the so-called common humanity, he saw them, too. Clearly. And he had the street level credibility to get them in his sights, and his assessments of what fuels ignorance, fear, and violence revolves around one single thing: hatred.

Bukowski has, of course, long been an easy target, especially for the insufferable and self-appointed insiders of the literary scene. Sure, the macho posturing (although this dude at least knew how to throw—and receive—a punch, literally and better still, figuratively) is never a good look and looks worse the further it recedes in the rear-view mirror. And yes, the output, staggering as it is (listen, just the willingness to put the words down, day after day, separates the scribblers from the posers, the doers from the onanists with amazing networks who worry about everything except actually getting the work done), is hard to parse, and tends to separate readers into opposite camps: completists for whom too much is never enough, and the aforementioned prigs who would never sully their delicate sensibilities by reading any of his work, or admitting it’s any good.

The fact of the matter is, Bukowski’s fiction has aged quite nicely indeed; even surprisingly so, and everyone is of course welcome to pick and choose the poems of their liking, but even if his body of work consisted of a handful of poems (some beloved, others obscure), his legacy stands proudly alongside many, many academy-anointed lightweights (no need to name names, but suffice it to say, I find more joy and soul—and authenticity—in a single page of Bukowski than anything I’ve read by Jonathan Franzen).

Your mileage may vary, but listen to this and this and see if they make so much contemporary writing seem insular, technical, precise, derivative, and like another brick in the ivory tower that’s at once endless and two-inches tall.

It’s an enduring tribute to The Buk that his writings continue to inform, inspire and console. It’s our collective tragedy, as human beings, that much of his subject matter remains relevant, applicable and therefore actively ignored. Then again, as William Carlos Williams declared, for all time: “It is difficult to get the news from poems/yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.”

Which, inevitably, brings us to Trump. And, all the innocent bystanders asking the same question going back to at least 2015: how can anyone be attracted to this? How, at long last, can elected Republicans—even by their own seemingly unfathomable capacity for opportunism and shamelessness—continue to lick his fake gold boots? (That’s a rhetorical question: fear and expedience are the one-two punch that poisons democracy, and if you want to read more about that, just peruse The Washington Post and the New York Times right now).

The more puzzling question seems to be: who, exactly, are these millions of Americans whose lives are demonstrably impacted—for the worse—by every single Trump policy and initiative? And the answer is: they’ve always been out there, hiding in plain sight. Naturally, the internet has enabled them to crawl out of their rat holes and find solidarity in sheer numbers, as is true of any gang or cult. Obviously, from Fox News down to alt-right marches (and bro podcasts!), there are many cynical outlets profiting (in all regards) from exploiting their pain. And certainly, in Trump, we have the apotheosis of reality TV, media-made, substance-over-style cult of personality disorder to serve as both Pied Piper and demigod for the disenfranchised.

But make no mistake: they were always out there.

And special disdain, as always, for the third party curious (or third party passionate), those clueless rebels in search of a cause (preferably one that involves minimal effort and self-awareness), seeking reassurance that the overarching hostility informing each impulse, suffocating every second, is shared, is rational, is noble. That there’s a meaning in the meaninglessness; the meaninglessness is the meaning. That petulance is resistance, that their fragile self-regard is worth burning down the whole house.

As craven, selfish and short-sighted as many of our elected officials have been this last decade (or forever, if you like), don’t kid yourself about what’s at stake. Mediocrity and mendacity, appalling as these options are, still function as bruised and repurposed life rafts in times like these. And things stand to get a lot worse. Of course, the people who will feel it first are the people who are already crammed into the dirty and desperate margins. The people who will get it next are the ones whose understandable outrage is (typically, predictably) misplaced. And, with torches in hand, they will merrily lead the sociopathic foxes to the henhouses, where there is still unfinished business to attend to. Finally, for those whose fat wallets help them fall upward (every time), they will roll up their sleeves and get back to what they do best: making sure that everything they’ve got stays got.

No one is coming to save us. But the artists will be, as always, on the front lines. They always have been. Here’s hoping we can find their work (everything up until this moment; everything going forward) consoling, inspiring, empowering. It’s up to us to create the type of world we want to have; always has been, always will be.

Chaser: Two poems, by me, about Bukowski—and other stuff.

Charles Bukowski’s Bounty (originally published in The Linden Review, available in The Blackened Blues)

You could write a poem about this:

That was the story of his life.

The story of his stories, something more

authentic than life, which is what Art can be.

Failure a half-empty amphitheater where ideas are born.

Anyone can orchestrate chaos but it takes guts

to own it, even if you can’t describe or explain it.

Between spilled beers and bruised hands there’s a question:

What kind of world would you create, even if you couldn’t?

Take that mattress, out in the street, second-hand

salvation for those disinclined to inquire, but unafraid

to inherit; in this part of town everyone knows shit

You throw into a dumpster doesn’t go there to die.

There’s always someone hungrier or less happy, someone

who will not go quietly into that precarious night,

grateful to have the things you no longer need.

The women were not unlike the poems and stories,

they were the gold you spun from the machine we call

Misfortune, or being brave enough to figure out you own time

even when you can’t make money; money and time own you

Unless you flip the script, sucking & fucking the sweetness

Life lets you steal when it’s looking the other way.

Content to sleep or screw or imagine better realities, lying

on a sullied mattress, unworried by their stains or the untruths

they could tell, contaminating you in unintended ways, because

we share everything anyhow, the ugliness most of all.

And miserable men become mice scurrying away from that evidence,

scared to reconcile the ways we made these fictions of ourselves

in our own likeness way before the world ever got involved.

And that’s why well-fed and wordless sheep pace silently inside

extravagant pens, erected to secure them from all the surprises

cops and cars and banks and bibles can’t protect or serve.

Or prevent the moon from sweet-talking the tides to turn or

the sun, setting without comment over shallow graves dug

With dirty fingernails, bleeding insolently onto dry-cleaned

suits: symphonies of all the seconds and cents spent, hoping

to hide the sick and satisfied smile of a Universe that will throw

all of us, ultimately, into immaculate recycling bins where,

once we die, starving saints turn us into stories and poems.

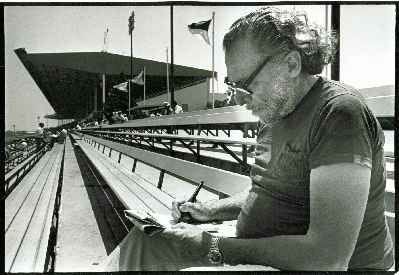

Henry Chinaski’s Horses (originally published in in JMWW, also collected in The Blackened Blues)

He couldn’t face the words, he wrote,

until he made it back from the track.

For a man famous for his refusal

to use metaphors, telling it straight like a tire iron,

this one kind of crept up on him, like they do.

Sort of the way the so-called real world punches suckers.

But perhaps that’s still too affected by half, since

the only thing, we know, worse than too little

Truth is too much of the same old shit.

Anyhow, Hank had his horses and his handicaps,

like all of us, no matter what we tell ourselves.

Whether it’s humping a desk or hustling the Morning Line,

or finding other ways to avoid assenting to work

altogether, we all need patterns and schemes.

Because by regulating our routines, they free up aspects

of ourselves—otherwise unengaged, like our dreams and

imaginations:

Or else we’re out of time, out of our minds.

So Hank had his horses and they told him who he was

on any given day: a winner, a loser, a player—and blinkered

or busted or flush, he returned to his humble post position and

that typewriter, waiting for him and placing its own bets:

Was the master in form? Pulling up lame? Wielding his whip?

Could he coax them through the muck, past the front of the pack?

Ending with the ultimate trifecta: booze and women and words.

(Then pause for a money shot, parading past the Winner’s Circle.)

Success is a salve that quenches a cultivated kind of thirst, and

what matters, finally, isn’t how you walk through the fire, but

the resolve to put your feet forward in the first place,

urging all those ideas to sneak up like solved secrets:

Reminders that even Long-Shots need somewhere to go,

Some way to live.