Jamie Muir, RIP

An extraordinary improviser who made the most of his brief moment

King Crimson was incapable of half measures, and the world’s always been richer for it. Debate will, fortunately, always ensue about what’s their best album, finest hour, most influential track, etc. But few real fans would argue that 1973 wasn’t an artistic culmination, not only for the band, but the movement they did as much as any band to define and represent.

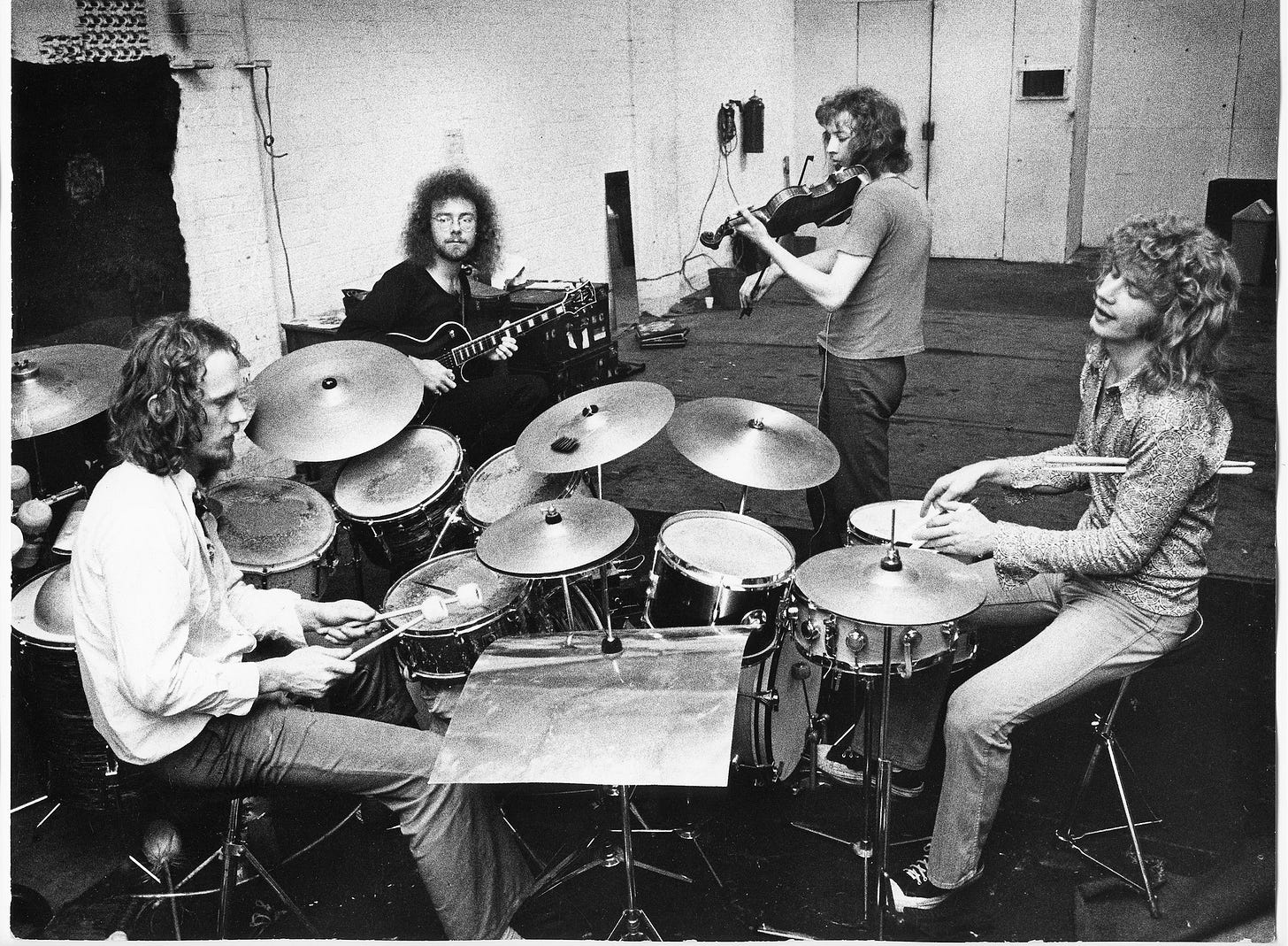

First they borrowed Jon Anderson (to sing on Lizard—more on that album here); then they inherited Bill Bruford once the great drummer bowed out of Yes. But nothing Yes—or King Crimson for that matter—had done to this point could have anticipated Larks’ Tongues in Aspic (the title alone an eccentric ode to the creative path less traveled). Most of the work made during the prog-rock era can be described to some extent, especially when it is categorically dismissed as pretentious noodling. But this song (actually part one of two, and while part two is magnificent in its own way, that riff-laden workout is much more straightforward than the kitchen-sink sensibility of part one) is a high water mark for the ideas, artistry and inspiration that define the best music of this time. As ever, Robert Fripp’s guitar guides the journey, downshifting from proto-grunge shrieking to jangling melodicism. But it’s the exotic violin contributions from David Cross and the tumultuous percussion stylings of Jamie Muir that take this track to that other place.

The song travels from placid to ominous (the languid, building menace of Fripp’s entry manages to almost be frightening), and then, after the bird calls and an invocation of the Far East, the ultimate postmodern touch: urgent, scarcely audible voices (from a radio? movie?) are looped and spliced, becoming gibberish that somehow makes perfect sense. As the song winds down, courtesy of Muir’s ethereal glockenspiel, a gentle chime (like a grandfather clock) washes over and out, and you are left wondering what hit you.

From the aforementioned Bill Bruford:

“Jamie Muir died today 17.02.2025 in Cornwall, UK, with his brother George by his side. From Bill:

Jamie was the drummer/percussionist with whom I worked on the King Crimson album ‘Larks’ Tongues in Aspic (1973). He had a volcanic effect on me, professionally and personally, in the brief time we were together many years ago – an effect which I still remember half a century later. I’m sorry we lost touch, but his departure from our working relationship was so sudden and unexpected, I sort of assumed he didn’t want anything more to do with me and my colleagues in King Crimson!

He was a lovely, artistic man, childlike in his gentleness. There was probably a dark side underneath. It could be be glimpsed as he climbed the PA stacks in a wolf’s fur jacket, blood (from a capsule) pouring from his mouth, on a rainy Thursday night in Preston, Lancs., to hurl chains across the stage at his drumkit. One of these Robert Fripp will tell you, only narrowly missed him.

His conversations with Jon Anderson at my 1973 wedding party, in Jon’s words, ‘changed my life’. Jamie also changed mine.

I consider it a privilege to have known, and benefitted from the company of, a man of such quiet power, even briefly. He struck me as one of those about whom one might truthfully say he was a beautiful human being. He will be much missed. Goodbye, Jamie.”

From the maestro himself, who deserves the first and last word on this matter, Robert Fripp:

“RF: Jamie's family were recently in touch, and generously so, to notify me of Jamie's process. My reply...

When Jamie left King Crimson in early 1973, he sent me a postcard and on the front: All part of the rich tapestry of life.

And on the back: Coo-ee. Jamie.

If you feel it appropriate, and not intrusive in any way, please say to Jamie...

All part of the rich tapestry of life.

Coo-ee. Robert.

Yesterday evening this e-mail...

"Jamie died this afternoon. His brother, George, was with him and this morning read Jamie your lovely words. He said that Jamie cracked a smile".

RF: Jamie Muir was a major, and continuing, influence on my thinking, not only musical. A wonderful and mysterious person. Of the five members of KC 1972, Jamie had the greatest authority, experience and presence.

Fly well, Master Muir.”

Like Roy Batty in Blade Runner, Muir was a light burning twice as bright and less than half as long. Six months to be precise: he was in and out of King Crimson before they—or anyone—could fully appreciate what hit us; the unavoidable, unbelievable, unforgettable evidence of his short but sublime contributions will endure, and are inseparable from an apex moment for prog rock.